Household displacement after disasters

Overview

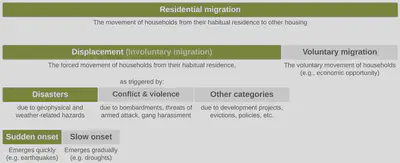

Over 265 million people were displaced due to disasters between 2008 and 20181. In the forthcoming years, the annual number displaced is expected to increase, driven by poorly-managed urban growth in hazard-prone areas2 and potentially exacerbated by climate change3. Despite this scale of human impact, most disaster risk assessments focus on direct economic losses, a metric that often highlights the wealthiest as the most at-risk. However, the reality of disasters is that the poor are disproportionately affected4, and mitigations informed primarily by economic loss may deepen existing inequalities. This research proposes to quantify disaster-induced displacement; a more equitable risk metric to depict the human toll of disasters.

Research themes

The importance of duration

Most statistics regarding population displacement following a disaster event provide single snapshot values, often representing a peak estimate during the emergency phase. However, the duration of displacement is essential for understanding the human impact. For example, large- scale displacement in the form of evacuations before a storm can save lives and be followed by mass return shortly afterward. In contrast, a devastating event such as an earthquake could damage or destroy a significant proportion of the residential building stock, causing occupants to seek alternative accommodations for months to years. Not only does this type of protracted displacement pose a significant disruption to the livelihoods of affected households (e.g., lost income, interrupted education), but the consequences can ripple out into the larger community (e.g., outmigration and urban blight, lost economic production). Therefore, a key objective of this research is to refine our understanding of household displacement duration in disasters.

Determinants of household return

Disasters are life events that can subject households to key decision points, such as: whether to evacuate, where to seek shelter, whether to return/wait/relocate, and whether to stay or resettle. From a literature review of household return after disasters, the following categories of determinants have been identified.

| Category | Determinants of return | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical damage to the built environment |

| |

| Psychological & social phenomena |

| |

| Household demographics |

| |

| Pre- and post-disaster policies |

|

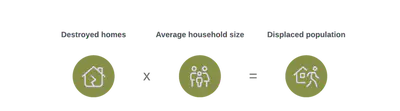

The role of housing damage

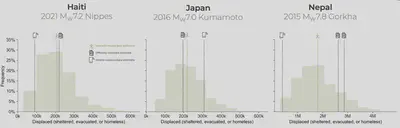

Disaster literature offers a clear consensus that housing damage is a primary driver of household displacement of disasters, both for initial displacement and longer-term displacement. However, additional factors (e.g., place attachment and housing tenure) have more recently been proposed as highly influential for household return in the recovery phase. Despite the range of factors beyond damage that have been proposed to influence household return, standard practice in disaster risk analysis is to solely consider housing damage. That is, the number of destroyed homes is multiplied by the average household size to yield an estimate of the displaced population.

I benchmarked predictions of household displacement based solely on housing damage to understand the extent to which such simplified models can explain the phenomenon. The scenario model estimates showed some promise to predict potential long-term housing needs. However, quantifying displacement duration remained a clear challenge as official reports lacked this information and model estimates similarly lacked a time component. Mobile location data could theoretically fill the data gap on duration, but the benchmarking results indicate that further investigation is required on such data-driven methods.

The full results of the benchmarking study are available in a journal paper and a conference paper.

Predicting displacement durations

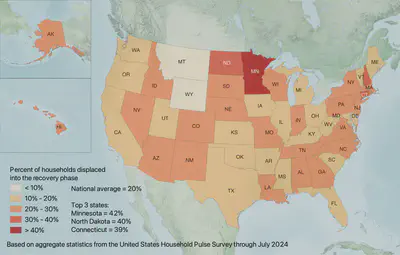

According to new data from the United States Household Pulse Survey (HPS), approximtely 1.1% of households have reported being displaced in recent disasters. However, the rates of disaster displacement vary widely state-by-state.

The vast majority of displaced households returned quickly: 43% within a week and an additional 23% within a month. However, others faced more protracted displacement: 20% took longer than one month to return and 14% had not returned by the time of the survey.

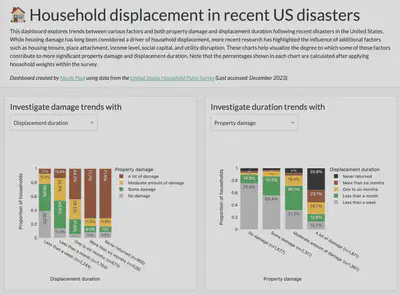

The availability of microdata from the HPS allows us to explore trends between displacement duration and return outcomes with potentially relevant factors such as: property damage, lifeline disruption, household demographics, and area-based attributes. To explore these trends, please refer to my interactive dashboard.

With the microdata, we can additionally fit predictive models and evaluate their performance. In our study, we propose three alternate models, which range in complexity and predictive power:

TreeP: A classification tree model that predicts return outcomes with a minimum number of predictors related to physical factors.

TreeP&S: A classification tree model that predicts return outcomes with a minimum number of predictors related to physical and socioeconomic factors.

ForestP&S: A random forest model that predicts return outcomes considering all predictions related to physical and socioeconomic factors.

The ForestP&S model additionally allows us to highlight the importance of different physical and socioeconomic factors to predictions of displacement duration and return. These model explanations confirm that property damage is a primary driver of displacement outcomes. However, they also indicate that some socioeconomic factors are critical to consider, such as a household’s tenure status and income level. Additionally, some factors (e.g., physical immobility, household sizes of 8+, educational attainment levels of less than high school) were associated with more negative outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research is partly funded by the University College London Overseas Research Scholarship (ORS) and the Willis Towers Watson Research Network.

IDMC. 2019. “Disaster Displacement - A Global Review, 2008-2018.” https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/disaster-displacement-a-global-review. ↩︎

IDMC. 2017. “Global Disaster Displacement Risk - A Baseline for Future Work.” https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/global-disaster-displacement-risk-a-baseline-for-future-work. ↩︎

IPCC, ed. 2012. “Summary for Policymakers.” In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation, 1st ed. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139177245. ↩︎

Hallegatte, Stéphane, Adrien Vogt-Schilb, Julie Rozenberg, Mook Bangalore, and Chloé Beaudet. 2020. “From Poverty to Disaster and Back: A Review of the Literature.” Economics of Disasters and Climate Change 4 (1): 223–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-020-00060-5. ↩︎